The term ‘biometric data’ is defined in Article 4.14 GDPR. Accordingly, biometric data are “personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioral characteristics of a natural person, which allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person”. The definition suggests that for personal data to be considered ‘biometric’ they need to satisfy fourcriteria[1].

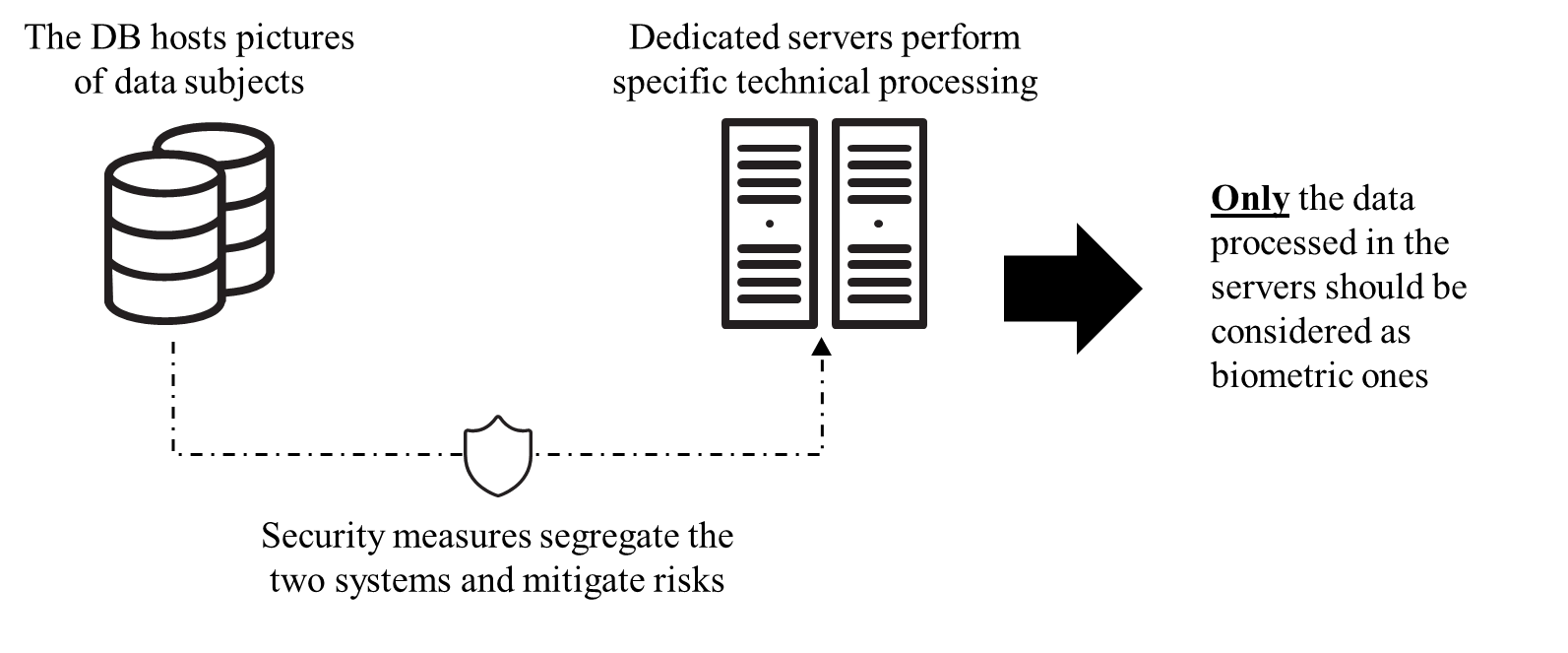

First, they need to amount to ‘personal data’, defined in Article 4.1 GDPR as “information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person”.Second, they require ‘specific technical processing’to extract the information from the raw data source (for instance, extracting facial features from a picture to measure them).Recital 51 of the GDPR states that the “processing of photographs should not systematically be considered to be processing of special categories of personal data as they are covered by the definition of biometric data only when processed through a specific technical means allowing the unique identification or authentication of a natural person”.Thus, biometric data short of ‘specific technical processing’ do not amount to biometric data in the context of the GDPR[2].However, even when data do not amount to biometric data at a certain stage, they might be part of a data processing that makes thembiometric data at a later stage. For instance, a database might host pictures that will be used to perform biometric identification through specific technical processing at a later stage (thus, not amounting to biometric data yet). Imagine a scenario in which said database is directly linked tothe system that performsthe biometric identification (see also section Biometric System). In this case, unauthorized parties might exploit this link to access biometric data. For instance, they mightexfiltrate the(non-biometric) pictures hosted in the databaseand, after having violated the system that performs the biometric identification, they might run the picture through it and perform the biometric identification, thus getting access to the biometric data. In this scenario, a weak security ensures that external parties can obtain biometric data even if these biometric data have yet to exist.Data controllers should approach this from a risk-management perspective (see the “Integrity and Confidentiality” subsection in the Principles section of the General Part of these Guidelines). If they cannot guarantee appropriate risk mitigation to the non-biometric data (i.e., exploitation risks) then these datasets should be considered as biometric ones and be subject to all the legal requirements, even if they don’t fulfil – by themselves –the criteria for being considered biometric data.

Biometric data scenario 1

Biometric data scenario 2

The third criterion pertains to the features of the data subjects that are captured through the specifical technical processing mentioned above. These features can be ‘physical’, ‘physiological’ or ‘behavioral’, and are different from accidental qualities such as the address of the data subject, its location at a given moment, employment data, etc.The fourth and last criterionstates that for personal data to be considered biometrics they need to allow or confirm the unique identification of a natural person. Indeed, biometric data do not necessarily uniquely identify individuals per se. For instance, biometric data could be used to distinguish between humans and animals, or between men and women[3]. However, differently from other identifiers such as names or identification codes, the processing of biometric data does not return a clear-cut identification.Rather, it allows the identification of individuals with a certain degree of probability. According to an established view, data should be considered as biometric ones “even if patterns used in practice to technically measure them involve a certain degree of probability”[4].

References

1On the analysis of the definition provided in the GDPR, seeC. Jasserand, ‘Legal Nature of Biometric Data: From “Generic” Personal Data to Sensitive Data’, European Data Protection Law Review 2, no. 3 (2016): 297–311, https://doi.org/10.21552/EDPL/2016/3/6. ↑

2Scholars debate if this should be applied as well to technical processing that are prerequisite for identification, such as mere storage in databases. See for instance,Kindt, Having yes, using no? About the new legal regime for biometric data, Computer Law and Security Review, 34, 2018, pp. 523-538. For an analysis of the issues around format other than photographs see AndrasNautschet al., Preserving privacy in speaker and speech characterisation, Computer Speech & Language, 58, 2018, p. 445. ↑

3See for instance ‘14 Misunderstandings with Regard to Identification and Authentication’ (Agencia espanola proteccion datos, European Data Protection Supervisor, June 2020), 3. ↑

4Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, ‘Opinion 4/2007 on the Concept of Personal Data’, 2007, 8. See also Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, ‘Opinion 3/2012 on Developments in Biometric Technologies’, 2012, 6. ↑