IoT: Ethical and legal requirements regarding data protection

Main author: Iñigo de Miguel Beriain (UPV/EHU)

Supporting authors: Aliuska Duardo (UPV/EHU), Álvaro Anaya Rojas, Gerardo Pérez Laguna & María Carmen González Tovar (Everis Ciberseguridad)

Preliminary versions of this document were reviewed by Federica Lucivero (Senior Researcher in Ethics and Data at Ethox and the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities (Big Data Institute) and Irene Kamara (Assistant Professor Cybersecurity Governance at TILT)

Revised by Fruzsina Molnar-Gabor, Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften (Germany) and member of the European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies of the EU Commission.

Finally validated by Iñaki Pariente, former director of the Basque Data Protection Agency.

Introduction

This section of our ‘Guidelines on data protection ELI in ICT research and innovation’ (hereafter ‘The Guidelines’)provides Internet of Things (IoT) developers and innovators with advice about the actions they should take to comply with the legal requirements related to the development of IoT tools in terms of data protection. They aim contribute to mitigate the ethical and legal issues in this field. Needless to say, this part of the Guidelines (as the whole of them) is not an authorized interpretation of the regulations, but some best practise recommendations.

This part of the Guidelines can only be understood in the context of the whole tool (the Guidelines). There are several concepts that are not explored in this document, because they are addressed in other sections; we have referred to these wherever needed (references are highlighted in yellow). All sections are available on an interactive website

Disclaimer

This part of The Guidelines was written at a time when the ePrivacy Regulation had not been approved. It may happen that at the time of using this tool, the Regulation is in force. If so, it will be necessary to take into account the possible changes that this may have produced in the regulatory framework. Until the ePrivacy Regulation enters into force, a fragmented situation will exist. Indeed, supervisory authorities face now a situation where the interplay between the ePrivacy Directive and the GDPR coexist and pose questions as regards the competences, tasks and powers of data protection authorities in those matters that trigger the application of both the GDPR and the national laws implementing the ePrivacy Directive.

Preface

Some years ago, the Article 29 Working Party stated that “the concept of the Internet of Things (IoT) refers to an infrastructure in which billions of sensors embedded in common, everyday devices – “things” as such, or things linked to other objects or individuals – are designed to record, process, store and transfer data and, as they are associated with unique identifiers, interact with other devices or systems using networking capabilities.”[1]

As for today, ubiquitous, pervasive, internet of everything, are some of the qualifiers used to describe IoT. These adjectives are intended to illustrate that the interconnection between the physical and virtual world is happening and can happen at all levels. The new and emerging IoT technologies comprises, among others: intelligent transportation systems, connected health devices, drones, 5G wireless communication, etc. Even the most trivial everyday aspects of our lives are beginning to be permeated by IoT. From “smart” coffee machines to mobile apps that allow us to perceive smells

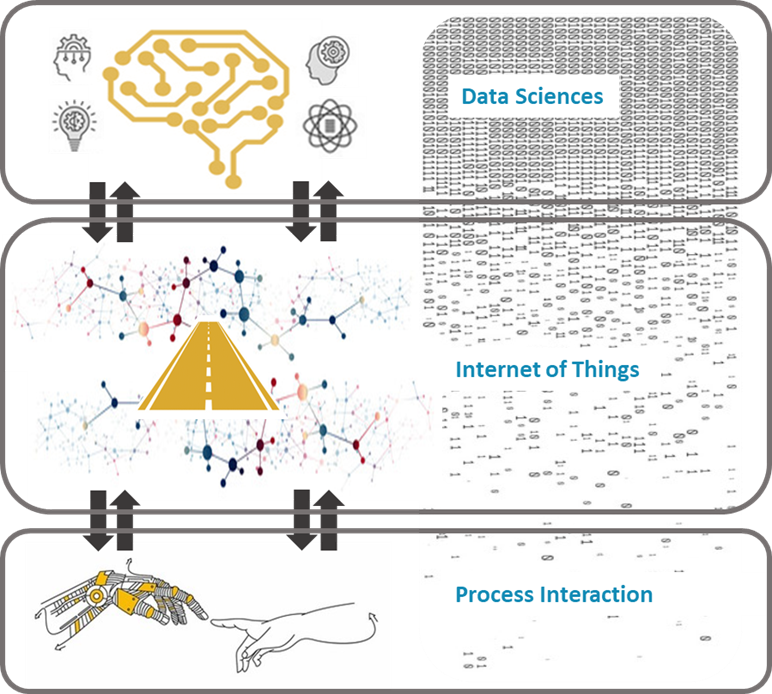

IoT is a special technology with strong ties to traditional Data Science technologies, but also with many differences that must be taken into account when defining a development model. Speed in data generation is one of the biggest differences between IoT and traditional Data Mining technologies. Although these technologies can become complementary, dynamic data processing encompasses shared networks to perform an analysis and response in real time, such as IoT does against an analysis of large volumes of static data.

IoT and Data Sciences landscape

This success in the field of data handling also presents a complexity in the development of new technologies, which is why it is essential to define processes to facilitate the development and implementation of IoT applications. Having models that help ICT developers understand the data protection legal framework, and that make it possible to identify, classify, and define the necessary tasks to address processing from the beginning of the development of solutions, gives the opportunity to reach a more efficient and structured implementation.

Covering all the ethical and legal implications of any IoT system in a guideline would be impossible.The qualification of IoT applies to a lot of different things. First, the devices themselves (step-counters, sleep trackers, “connected” home devices like thermostats, smoke alarms, connected glasses or watches, etc.). Second, the users’ terminal devices (e.g. smartphones or tablets) on which software or apps were previously installed to both monitor the user’s environment through embedded sensors or network interfaces, and to then send the data collected by these devices to the various data controllers involved. Furthermore, software tools are necessarily used to make the systems work.

It would be hard to address all the issues related to this wide framework. Thus, our workproposes a simplified model that makes it possible to help IoT system developers fulfil the personal data protection requirements settled by the European Charter of Human Rights, the GDPR and the complementary regulatory tools. Nonetheless, stakeholders, including designers, manufactures, network owners and marketers, must take into account the applicable laws and ethical guidelines that for each specific development, -both mechanical and information and communication systems- related to its concrete IoT system.

To this purpose, this Chapter of the Guidelines attempts to offer ICT developers a systematic and simplified view of how to meet the legal requirements of EU data protection law. This is done without neglecting ethical guidelines, adding IoT products the value of “empowering individuals by keeping them informed, free and safe”[2]. In this sense, the present document, draws heavily on the considerations of the Art 29 Data Protection Working Party Opinion 8/2014 on the on Recent Developments on the Internet of Things[3]; the Commission Staff Working Document Advancing the Internet of Things in Europe[4]; and the Baseline Security Recommendation for IoT in the Context of Critical Information infrastructures[5]. Notably, these documents are subject, in most member states, to a particular regulatory framework and represent different regulatory subject matter than the areas covered by the other guidelines. Furthermore, ICT developers should always keep in mind that the EU regulation on IoT will probably change in the next times. Consultation with their DPOs about possible changes and national particularities is always recommendable.

References

1A29 Working Party, Opinion 8/2014 on the on Recent Developments on the Internet of Things, 2014, at: https://www.dataprotection.ro/servlet/ViewDocument?id=1088 ↑

2According to the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, this is “is the key to support trust and innovation, hence to success on these markets”. Article 29 Data Protection Working Party Opinion 8/2014 Op. Cit. ↑

3Art 29 Data Protection Working Party (2014) Opinion 8/2014 on the on Recent Developments on the Internet of Things (SEP 16, 2014) https://www.dataprotection.ro/servlet/ViewDocument?id=1088. Accessed Nov 2020). Although this opinion predates the entry into force of the current GDPR, we consider that the assessments made at the time by the working group are still valid. This opinion provides the ethical-legal keys to guarantee privacy, without hindering the development of the IoT. ↑

4Commission Staff Working Document Advancing the Internet of Things in Europe, accompanying the Document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Digitising European Industry Reaping the full benefits of a Digital Single Market. European Commission N5(APRIL 19, 2016) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52016SC0110&qid=1610616372730 (Access Dec. 2020). ↑

5Baseline Security Recommendation for IoT in the Context of Critical Information infrastructures, ENISA 12 (2017), https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/baseline-security-recommendations-for-iot. (Accessed Nov 2020) ↑